Hot take: Most PhD students spend 6-12 months on literature reviews that nobody—including their advisors—will ever read in full. We all know it. We all do it anyway. And the academic system is complicit in this charade.

Let me be clear: I'm not saying literature reviews are useless. I'm saying the way we currently do them is theater. Elaborate, time-consuming theater designed to signal academic rigor rather than actually achieve it.

The Dirty Secret of Academic Literature Reviews

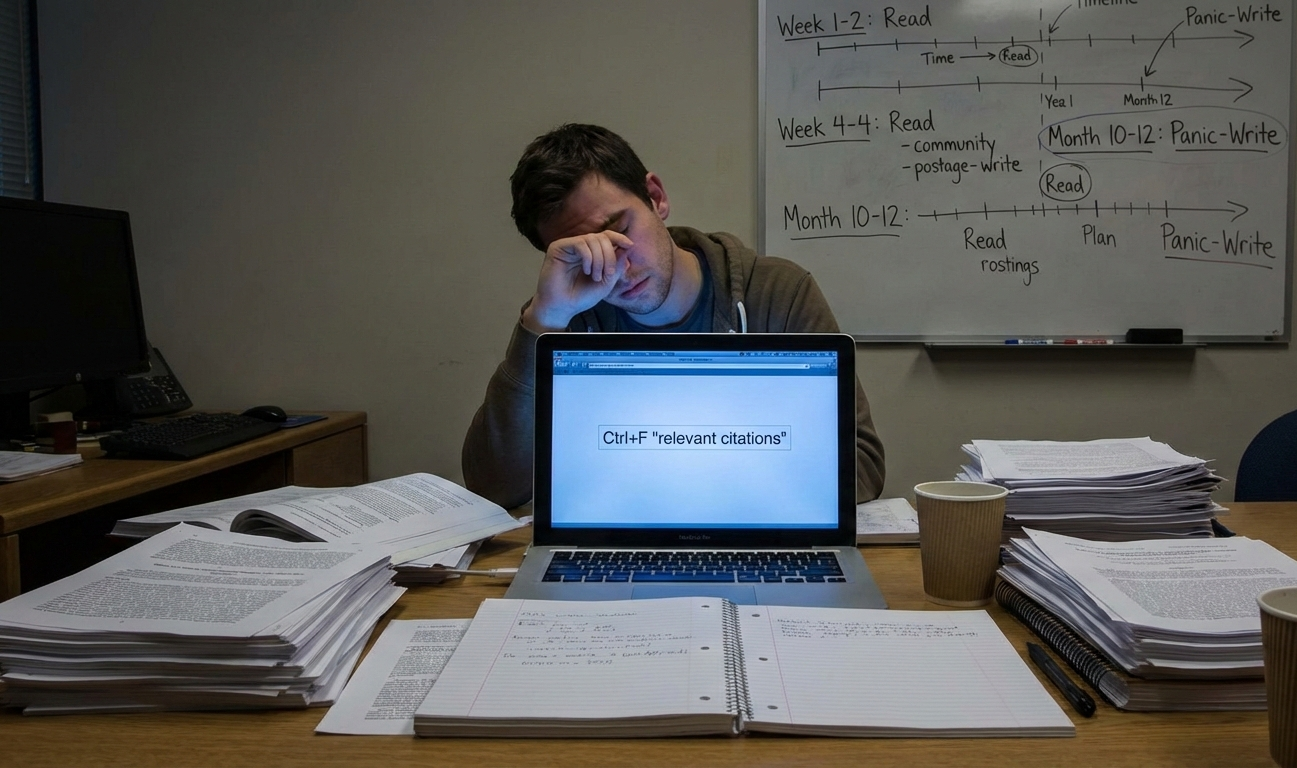

Here's what really happens during a "thorough literature review":

Week 1-2: You actually read papers carefully, taking detailed notes, feeling productive.

Month 2-3: You're skimming abstracts and conclusions, telling yourself you'll "come back to the important ones."

Month 4-6: You're Ctrl+F searching for specific terms, copying quotes you might cite, and adding papers to your bibliography that you've only read the title of.

Month 10-12: You're panic-writing a literature review section that synthesizes 150+ papers, 40% of which you only vaguely remember, citing claims you haven't actually verified, creating a narrative that makes it seem like you've mastered this entire field.

Your advisor skims it. Your committee members might read the first few paragraphs. Nobody checks if you actually read all 150 papers.

And here's the kicker: everyone in academia knows this is how it works.

We're Optimizing for the Wrong Thing

The academic system rewards the appearance of comprehensive literature mastery, not actual comprehension or synthesis.

Think about what we're actually incentivizing:

- Quantity over quality: "You need to cite at least 100 papers" (Why? Who decided this number?)

- Recency theater: Including the last 5 years of publications even when they don't add anything new

- Coverage obsession: Reading tangentially related papers just to prove you "covered the field"

- Citation padding: Citing papers you haven't read because other people cited them

The result? PhD students spend 25% of their doctoral program on a literature review that:

- Takes 12 months to write

- Will be read thoroughly by approximately 0.5 people (your advisor, maybe)

- Contains insights that could have been extracted in 6 weeks

- Teaches you more about academic performance than actual research

The Paper Reading Crisis Nobody Talks About

Let's address the elephant in the room: most published papers aren't worth reading in full.

I said it.

Here's the uncomfortable truth that every senior researcher knows but won't tell PhD students:

- ~40% of papers - Incremental contributions that could be summarized in 2 sentences

- ~30% of papers - Poorly written or poorly designed; you're reading them for completeness, not insight

- ~20% of papers - Solid work, but not directly relevant to your specific research question

- ~10% of papers - Actually deserve your full attention

But we make PhD students read all of them front-to-back anyway. Why? Because "that's how we did it" and "you need to put in the time."

This is cargo cult academia.

The Advisor Contradiction

Your advisor tells you to "read deeply" and "engage with the literature." But observe what they actually do:

- Skim 90% of papers

- Read abstracts and conclusions first

- Jump straight to figures and tables

- Use Ctrl+F for specific terms

- Rely on review papers to understand new fields

- Sometimes cite papers they haven't fully read (yes, even tenured professors do this)

Then they turn around and tell you to "be thorough" and "don't cut corners."

The hypocrisy is staggering.

They survived by developing efficient reading strategies through trial and error. But instead of teaching you those strategies, they make you suffer through the same inefficient process they did—as if struggle itself has academic value.

What Literature Reviews Should Actually Be

Here's my controversial proposal: A good literature review should take 4-6 weeks, not 6-12 months.

What should you actually be doing?

-

Read strategically, not comprehensively

- Start with 3-5 seminal papers and 2-3 recent review articles

- Identify the 10-15 papers that actually matter for your research question

- Skim everything else for coverage

-

Focus on synthesis, not summary

- Nobody cares that "Smith et al. (2019) found X and Jones et al. (2020) found Y"

- We care about: What's the debate? What's missing? Where's the opportunity?

- One paragraph of real insight beats five pages of paper summaries

-

Prioritize understanding over coverage

- Deep comprehension of 20 papers > surface knowledge of 200 papers

- Your research will be better if you truly understand the core concepts

- Citation count is a terrible proxy for literature mastery

-

Be honest about what you've read

- If you only read the abstract, cite it as background, not as evidence

- If you skimmed it, don't pretend you engaged deeply

- If it's a secondary citation, acknowledge that

The AI Tool Paradox

Here's where it gets really interesting: AI summarization tools are now good enough to expose the theater.

You can get a decent summary of 100 papers in a few hours. The academic system is freaking out about this because it reveals what we've known all along: most literature review "work" is just information processing, not deep thinking.

The knee-jerk reaction from academia: "AI tools are cheating! Students need to struggle through reading every paper!"

But why? If the goal is to understand the field and identify your contribution, and AI can help you process information faster, isn't that... good?

The real fear isn't that students will learn less. It's that we'll have to admit the current system is inefficient.

Hot take within a hot take: If an AI can replicate your literature review process, your process probably wasn't adding much intellectual value anyway.

What Should Change (But Probably Won't)

What advisors should do:

- Teach efficient reading strategies explicitly

- Emphasize synthesis over coverage

- Value quality insights over citation count

- Be honest about their own reading practices

What PhD programs should do:

- Set reasonable literature review timelines (6-8 weeks, not 6-12 months)

- Reward deep understanding of core papers over shallow coverage of hundreds

- Stop using paper count as a proxy for thoroughness

- Teach critical reading skills instead of assuming students will figure it out

What researchers should do:

- Stop pretending you read every paper you cite

- Share your actual reading workflow with junior researchers

- Prioritize papers that are well-written and clearly argued

- Write papers that respect your readers' time

The Uncomfortable Truth

The literature review in its current form is a hazing ritual masquerading as pedagogy.

It serves more to signal that you've "done the work" than to actually prepare you for research. We've confused suffering with scholarship, time spent with understanding gained, and citation count with intellectual depth.

And the tragic part? By the time you finish your PhD and realize this, you're now the advisor perpetuating the same system because "that's how it's done" and "I had to do it, so should they."

A Better Way Forward

I'm not saying literature reviews are pointless. I'm saying we should be honest about their purpose:

Purpose: Understand the field deeply enough to identify where you can make a contribution.

Not the purpose: Read every tangentially related paper to prove you're thorough.

Time it should take: 4-8 weeks of focused work.

Not the time it should take: 6-12 months of performative scholarship.

What you should produce: A synthesis that shows you understand the key debates and can articulate your unique contribution.

Not what you should produce: A 50-page paper summary document that nobody will read.

The tools exist now to process information faster. The question is: will academia adapt to use them for deeper thinking? Or will we double down on theater because "that's tradition"?

The Real Question

When you're six months into your literature review, drowning in PDFs, ask yourself:

"Am I learning and synthesizing, or am I just performing thoroughness?"

If it's the latter, you're not alone. You're just playing the game everyone else is playing.

But maybe it's time we changed the rules.

Disclosure: I know this post will piss off some people. Senior academics will say I'm advocating for shortcuts. Advisors will worry their students will use this as an excuse to do less work.

But talk to any honest PhD student or recent graduate. They'll admit I'm right.

The emperor has no clothes. The literature review is broken. And pretending otherwise helps nobody.

The question isn't whether this is controversial. The question is: when will we be honest enough to fix it?

What do you think? Am I wrong? Am I onto something? Have you experienced this in your own research? I want to hear both sides—tell me why I'm full of it, or tell me what I missed.

Further Reading (because even controversial opinion pieces need citations):

- If you want to learn actual efficient reading strategies, not what advisors pretend they do

- How to actually synthesize literature instead of just summarizing it

- The difference between comprehensive coverage and strategic selection

- Why some 10-page literature reviews are better than most 50-page ones